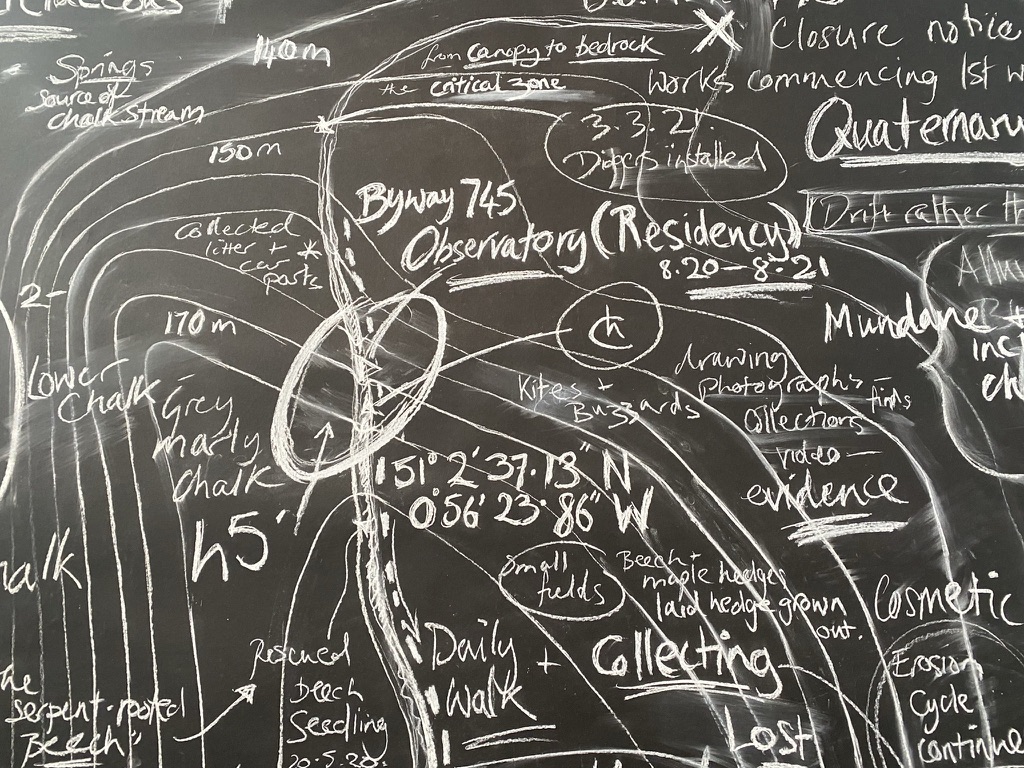

Since completing my Final Major Project, Byway 745 Observatory, for the MA in Fine Art at UCA Farnham, I have had time to reflect on the work and to present another iteration in a gallery context. I’ve also been able to publish a video of the installation for those unable to visit in person.

Making this video was an opportunity to guide the viewer around the space and use the camera to pick out the cross-references between objects, drawings, sculpture and the digital elements. I’ve used parts of the soundtrack from the video screened in the space to lay over the images, giving it more prominence. The 4 minute duration aims to point out the components of the piece without telling the whole story and I have been able to add it to my Postgraduate Showcase on the UCA website.

The full installation has been dismantled now but some parts of it are being exhibited in the James Hockey Gallery, the university’s public exhibition space. Titled Alt-terior, this show presents selections from twelve graduating artists’ final projects. One large space is inhabited by the diverse set of works rather than being compartmentalised as they were in the studio spaces. This has allowed new thresholds and connections to be established between the works.

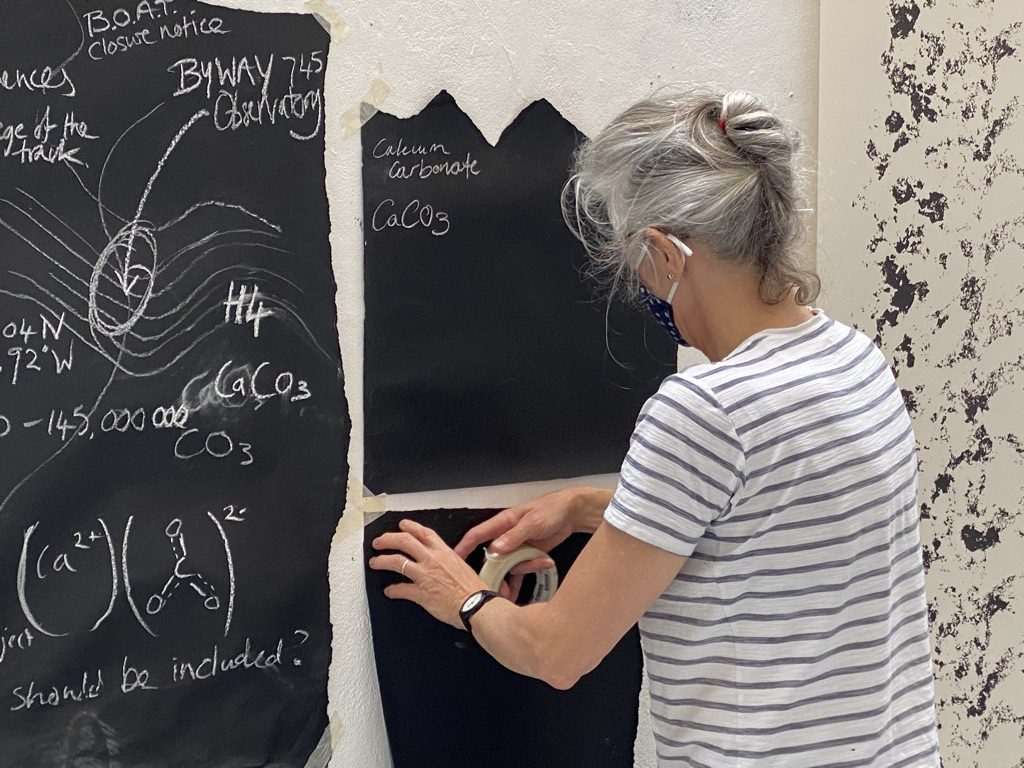

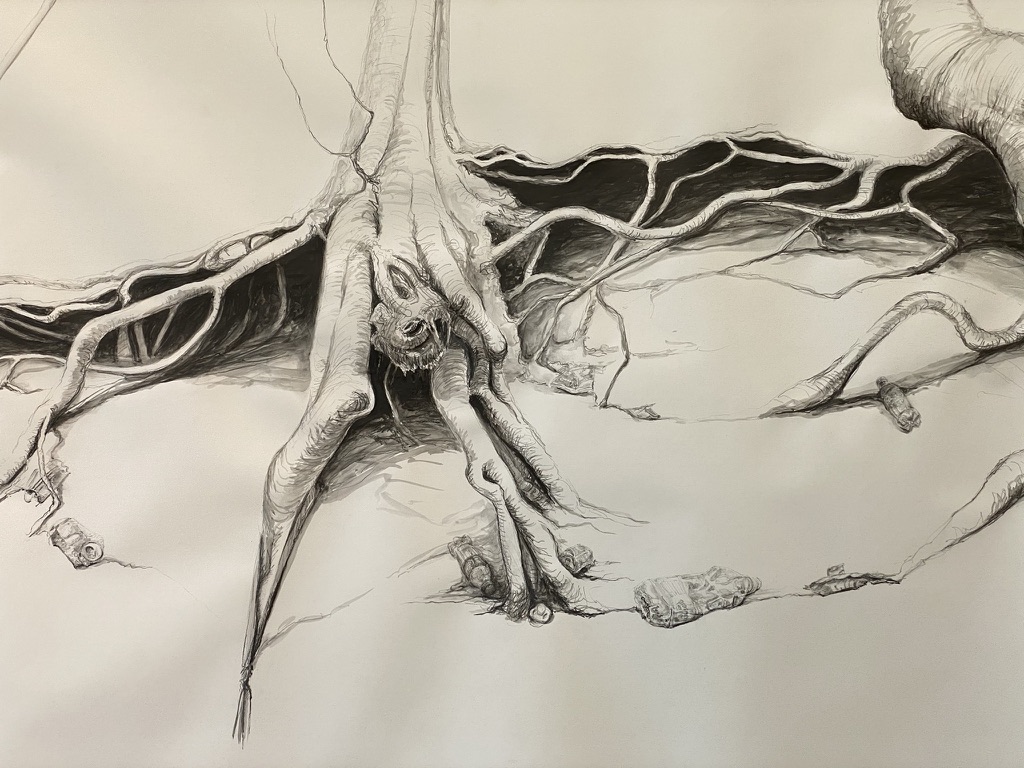

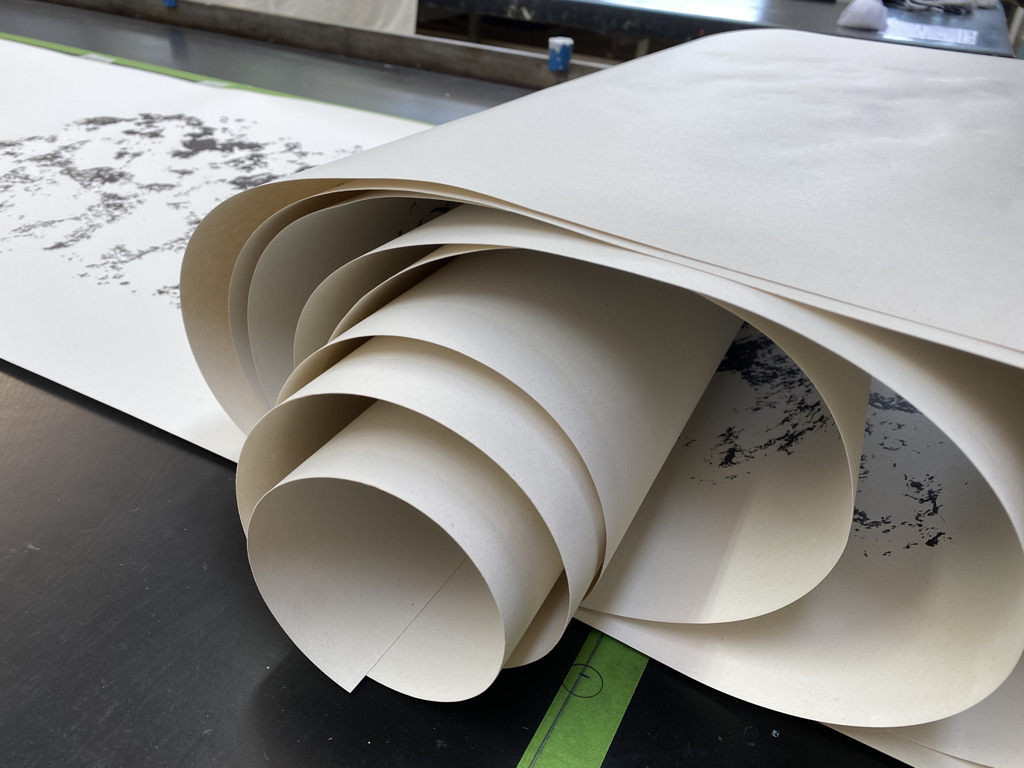

The three elements the curator chose from Byway 745 Observatory were the chalk drawing on black paper, the large gabion sculpture and the double screen video piece. I was allocated a corner to install the work at the far end of this long rectangular space. The drawing sits comfortably on that end wall, balancing the black and white photographs of Li An Lee opposite the back door of the gallery.

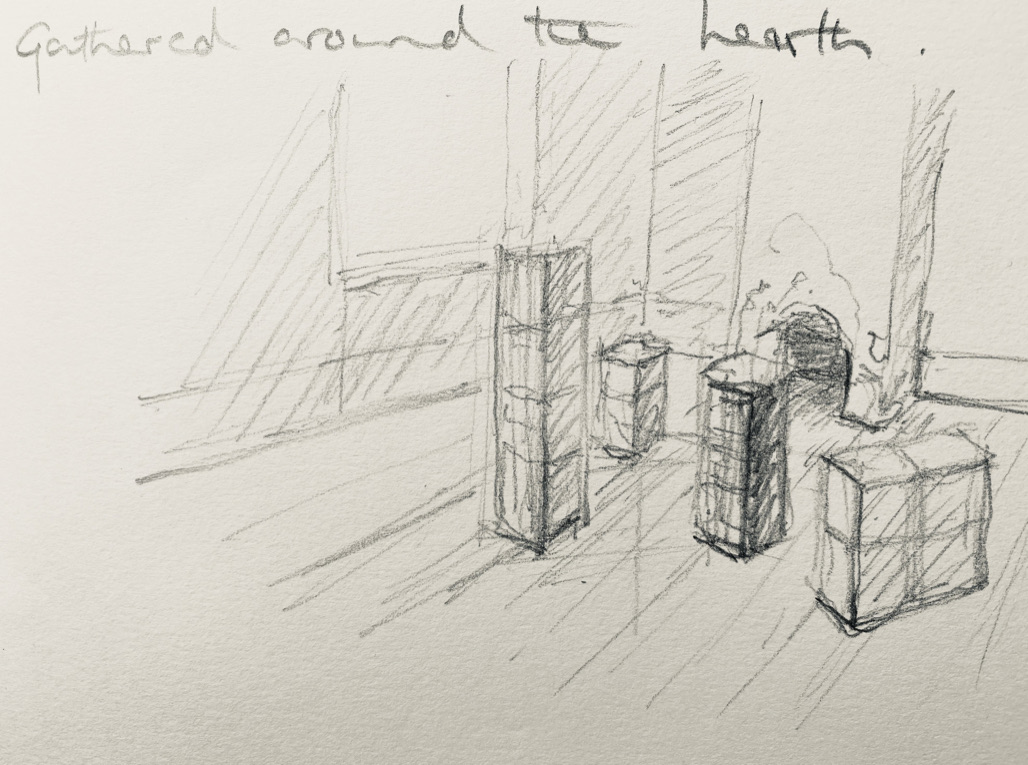

The choice of these three elements is a paired down iteration of the project that, interestingly, still manages to convey the essence of what it is about. The chalk drawing is no longer a work in progress and also becomes more of a focal point, having been given its own wall, visible from the far end of the gallery. Placing the gabion sculpture diagonally then links to the video screens on the adjacent wall. Those two videos combine to describe a slice of the ‘critical zone’, the space between lower atmosphere and upper bedrock, that the work observes. Ideally, the screen showing changes to the canopy should be larger and more horizontal, something I’ll explore the logistics of further for subsequent exhibitions.

The floor space in the middle of the gallery nearest my piece is occupied by Lucy Bevin’s The Uncanny Home, itself also a fragment reconfigured from a larger installation. That work speaks to mine across the space with its screened video angled towards the corner in which mine are screened, a connection that is made possible in this large open-plan space and throws up possibilities for further co-curation of our work.