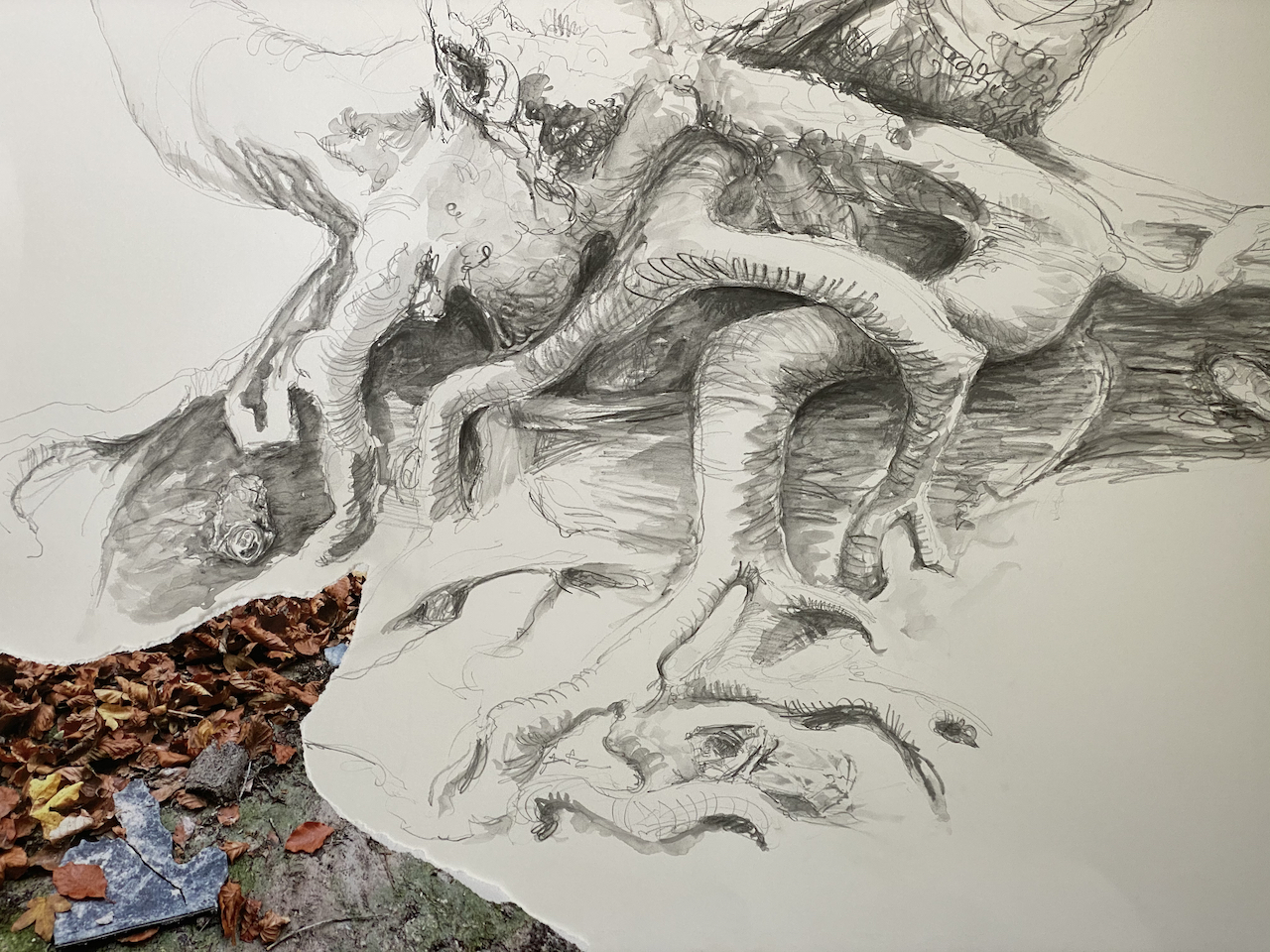

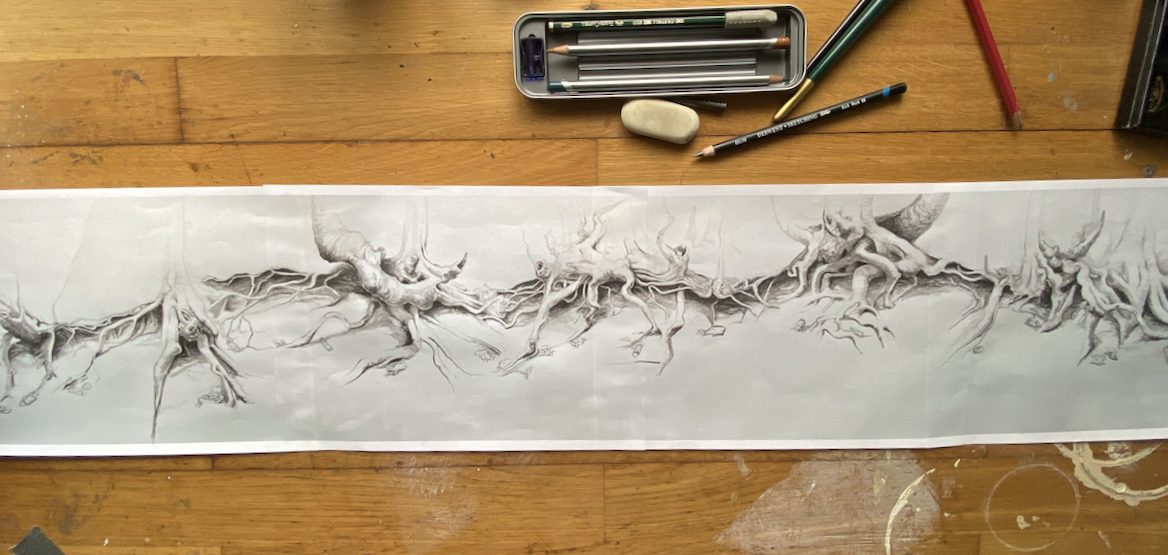

I have a large scale work in progress – a 7 metre long drawing using the line of beech trees that borders Byway 745. I’m in the planning stages of further work on this drawing, considering the various options for weaving imagery of the litter I’ve been collecting from the track beneath the line of trees.

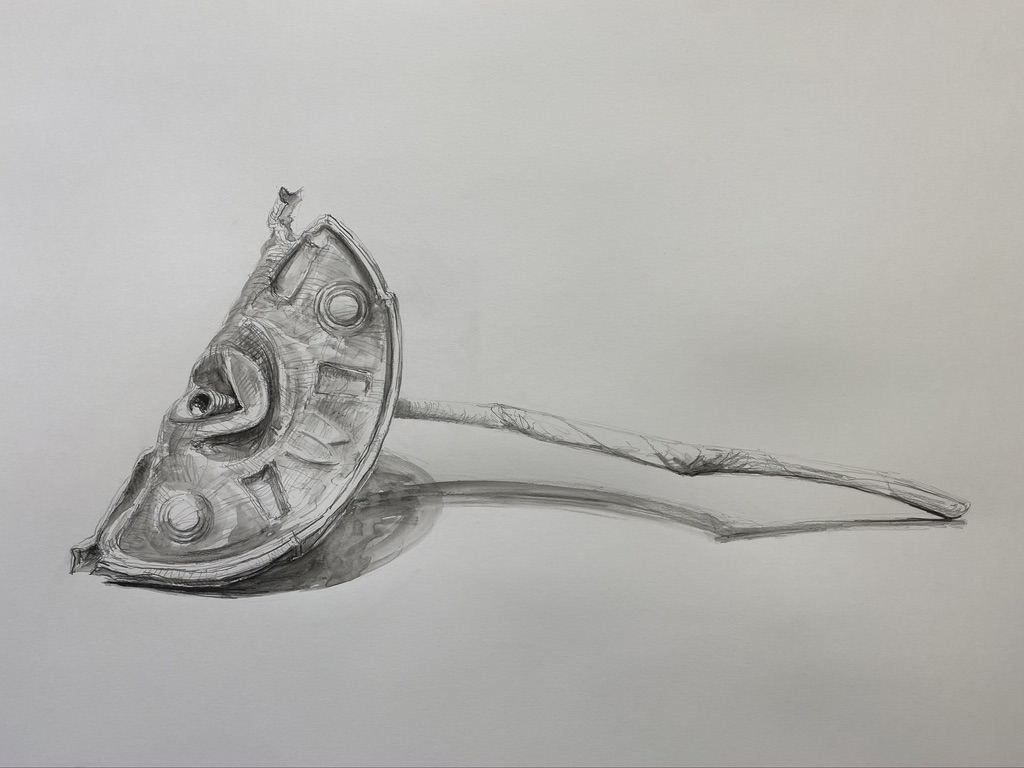

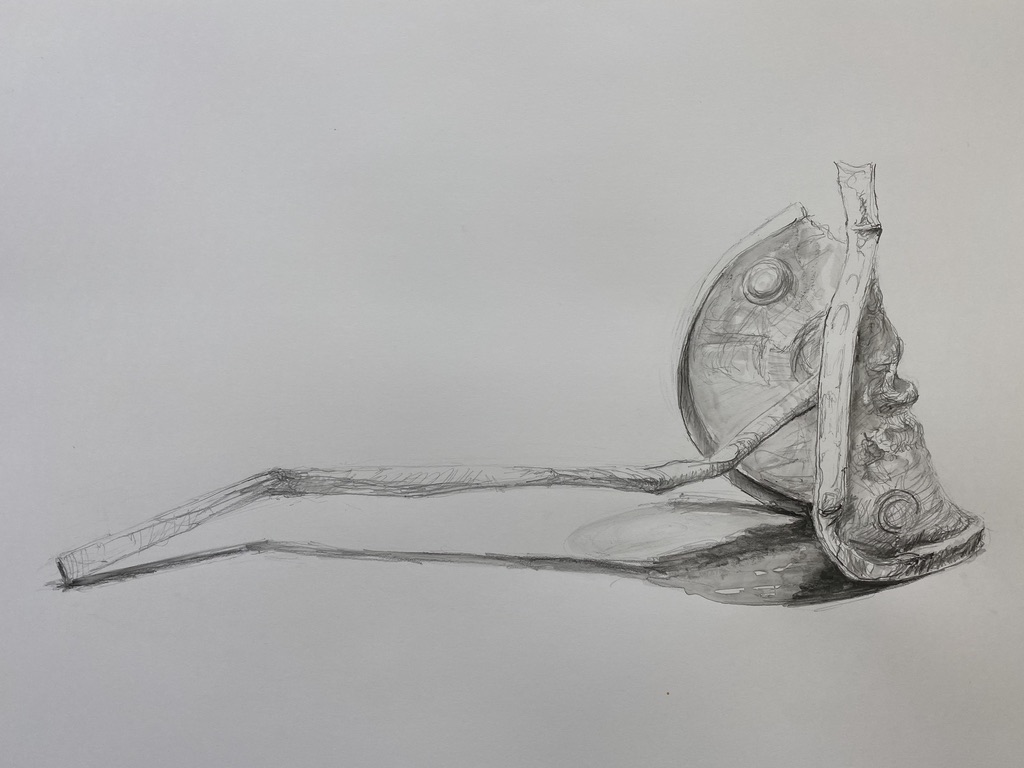

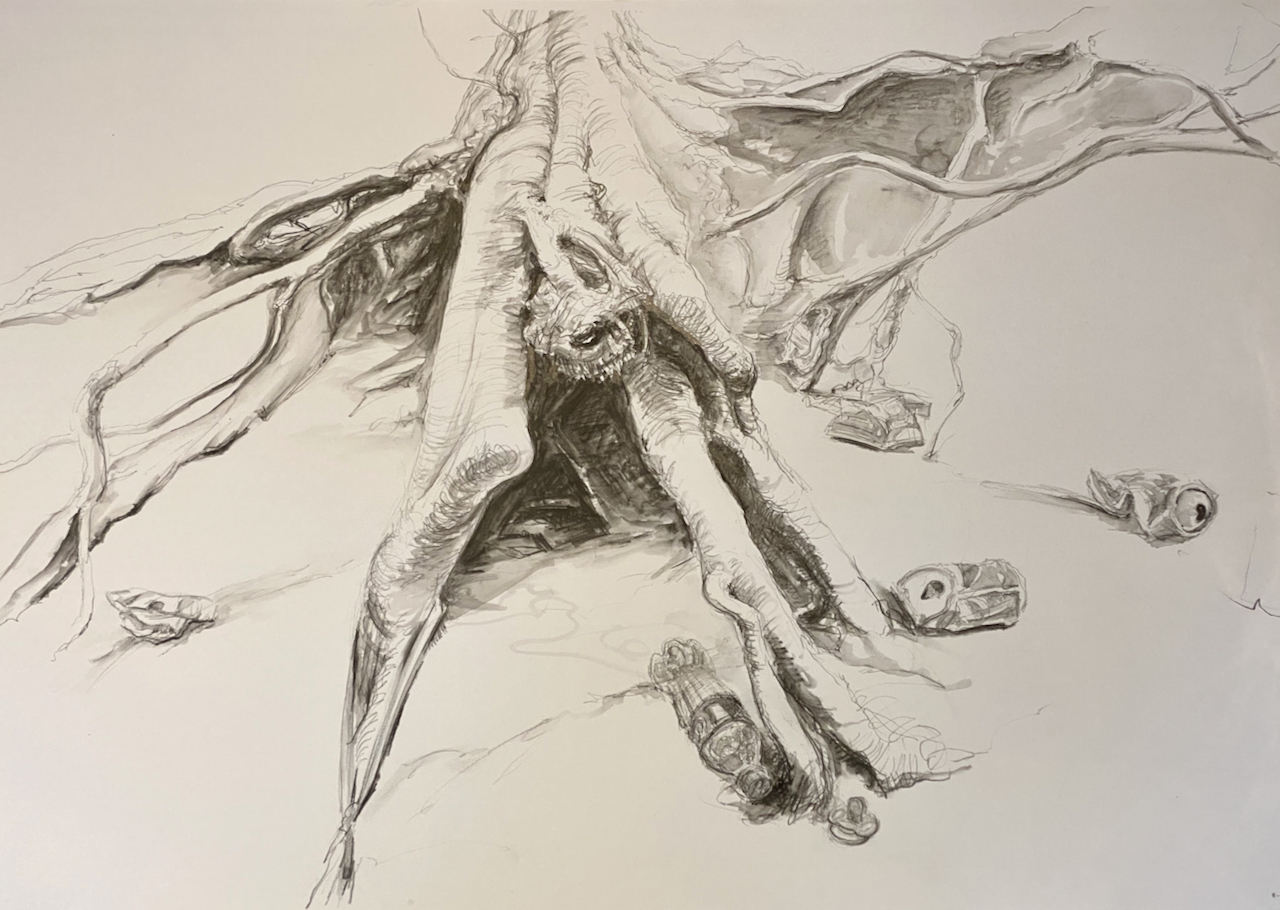

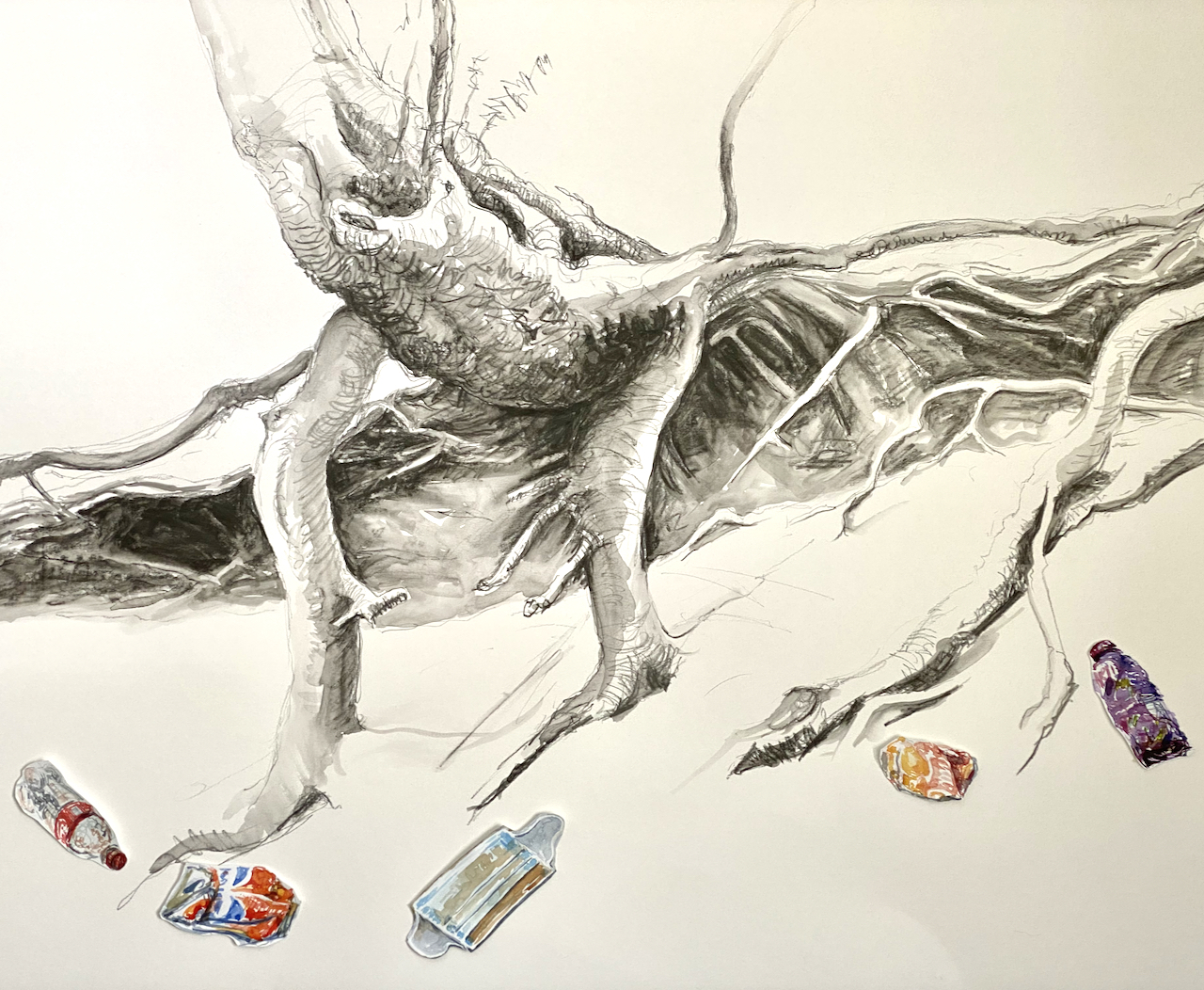

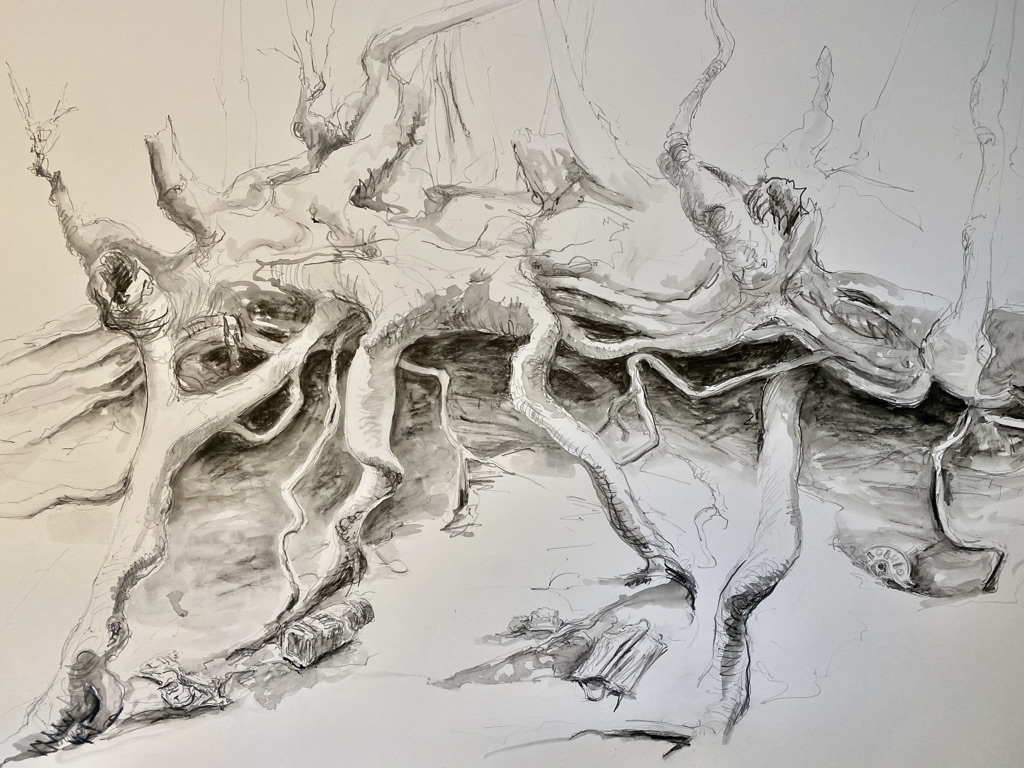

I have been drawing from observation in the studio using graphite and watercolour wash. Drawing directly onto the A1 originals to work out scale and positioning, to be transposed later onto the 7m drawing. The question of colour or no colour is the most vexing. The objects are often instantly recognisable from their colour, the ubiquitous reds of Coca-Cola or Stella Artois and the purple of Ribena, even if they have been crushed and partially destroyed. To help me decide, I have created temporary collages on the original graphite drawings with watercolours of the litter as well as with photographs of it.

After much deliberation, I have decided to stick to monochrome, using graphite and wash, as I did for the trees, so that the litter is not immediately obvious. As I weave the objects into the large drawing I may be tempted to use splashes of colour here and there but I’d like to treat them as part of the same ecosystem as the beeches. The man made objects that are found under the line of trees have been dropped as people pass up and down the track. They mark a passage of time but they also become stuck in a moment of time. In the city these flows of litter are part of a system, but in the countryside they are outside any system of collection and disposal. As Rosemary Shirley points out in Rural Modernity, Everyday Life and Visual Culture litter in the countryside ‘sits, it decays, and interestingly it sometimes becomes colonised by its new environment’ (Shirley 2016: 60). These photographs show just that happening as layers of leaves and mud cover the objects and moss begins to grow on them.

The litter marks evidence of human intervention in this landscape, along with that held in the shapes of the trees, once a coppiced hedge, and the bank beneath it which has been eroded by human traffic. I’m now ready to start the task of weaving a horizontal layer of new drawings across the entire length of the 7 metre drawing at the point where the roots emerge from the bank. I’ve made a rough plan on a photocopy and will have to work in sections on the floor. It is now time to get going with it.

All drawings and photographs by Liz Clifford.