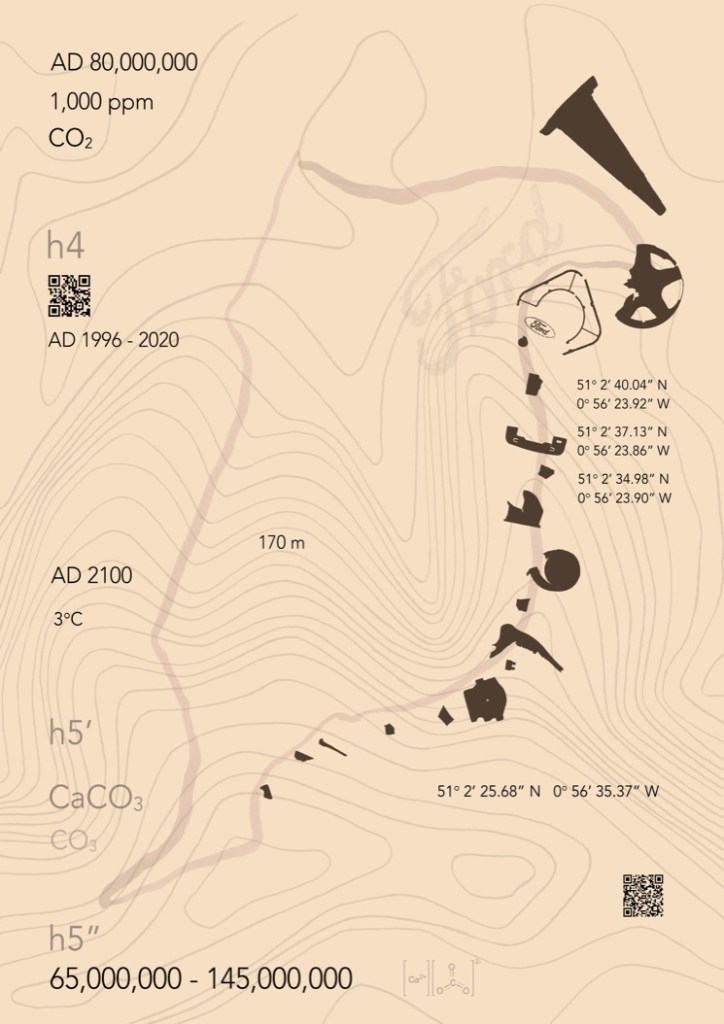

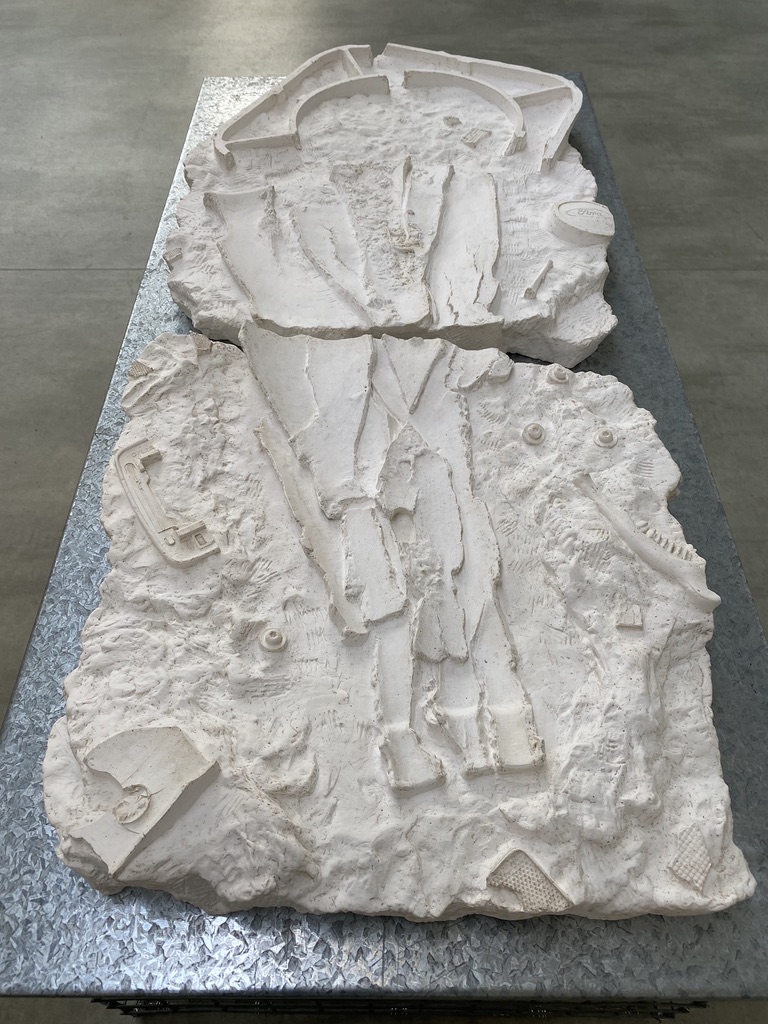

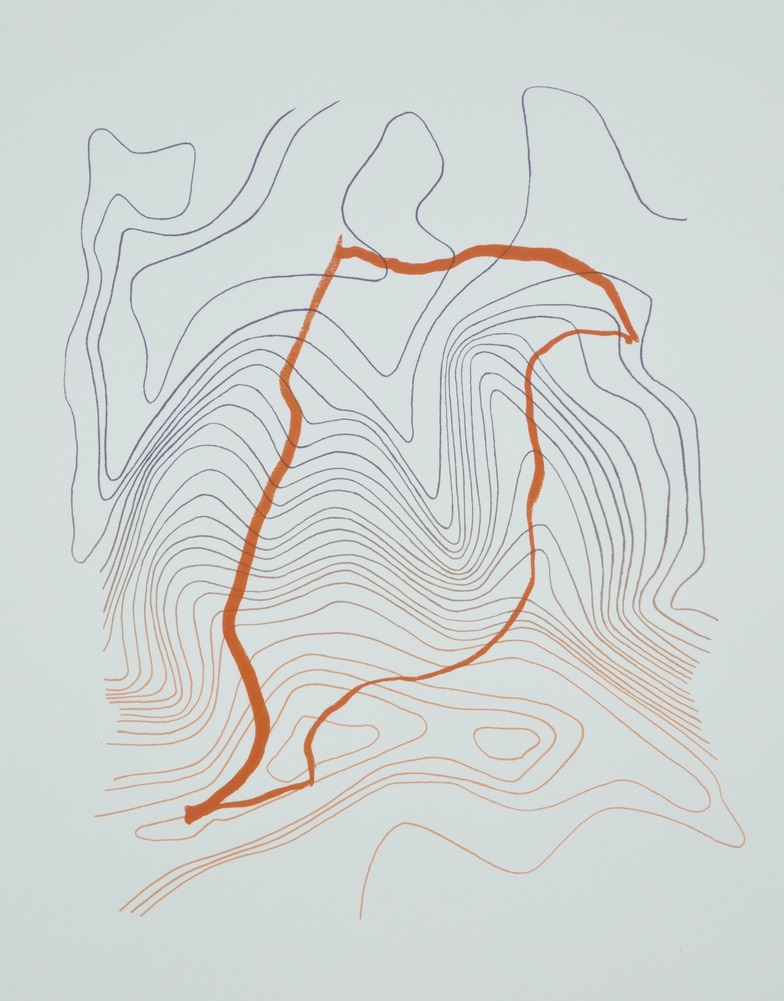

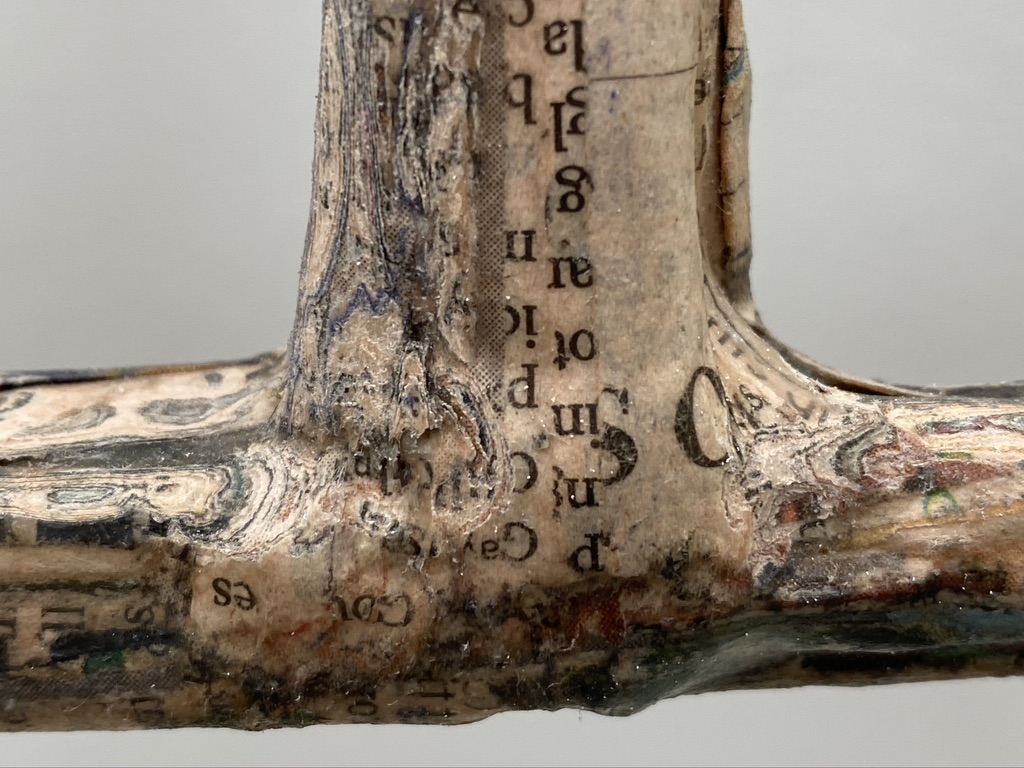

I’ve been building on my site specific project with found detritus as presented in my blogpost of January 4th. The latest intervention has involved taking hand built gabion baskets into the landscape and filling them with detritus from the two Rubbish Cairns I have been monitoring on Byway 745 since last summer.

Whilst lockdown against Covid-19 has been in place there has been a fall off in the amount of rubbish found but it hasn’t dried up completely. Old fragments are still surfacing and new litter is appearing. Tissues are more prevalent which feels particularly disturbing. See my previous post Under(cover) in which I discuss my audiovisual work dealing with these specific objects.

I was able to clear the Rubbish Cairns away totally into the two square gabions and fill the small rectangular one with storm damaged beech twigs. Interestingly, a passerby walker expressed his surprise that litter is left “out here” in this landscape. The idealisation of the countryside leads to disbelief that anything can ever be amiss, and outrage that it could be at all in a National Park. Rural sociologist Rosemary Shirley identifies this phenomenon in her book Rural Modernity, Everyday Life and Visual Culture (Ashgate/Routledge 2015) where she writes that “The presence of litter in the countryside….is not benign. It creates a range of emotional responses from slight annoyance to outrage, from nervous curiosity to actual fear.” A persistent nostalgia about the countryside is at odds with its contemporary reality, as a place of recreation and agribusiness, as well as a place to live, work and from where to commute.

Before removing the packed gabions back to the studio, I experimented with siting and configurations of the three. I started by placing them back where the chaotic piles had sat for the last ten months. Tidied away and contained at last.

Then I placed the forms on the most rutted and eroded part of the track, in a stack and in proximity to each other. This was the context in which the materials were originally found. The site of struggles with gravity, mud, wind and rain. Reviewing these photographs, I’m stuck by the proportion of manmade detritus to natural leaf form within the gabions, the technosphere and the biosphere. One more gabion of detritus would make for a representation of Jan Zalasiewicz’s one metre measure of the geological data of the Anthropocene – biomass makes up 5kg per m² whereas human produced detritus makes up 50kg per m². A really sobering statistic that he expands upon in his essay “The Anthropocene Square Meter” included in Critical Zones. The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth. 2020, eddited by Bruno Latour & Peter Weibel (MIT Press). Alternatively – only half filling the small gabion would achieve the same proportion.